Death of the master builder

St Peter’s Basilica. Notre Dame. The United States Capitol Building. What do these three iconic buildings have in common? They were all erected by “master builders”—part architect, part engineer, part building site supervisor—who designed them and oversaw their construction from start to finish. From medieval times to the Victorian era, this was the primary way buildings were constructed.

Master builders were true renaissance men—women were largely excluded from the field—like famed British architect Sir Christopher Wren (in addition to his extensive portfolio of churches, palaces, and libraries, he founded the Royal Society and taught Astronomy at Oxford). They had to understand every aspect of construction, from mathematics to masonry, enabling them to coordinate a team of skilled tradespeople to realize their vision. While the master builder would sometimes change over the course of the project—and often did, in the case of grand projects that took decades, if not centuries, to complete—there was always one point person in charge—someone who not only understood the vision for the whole but how every component fit into it.

[Image Credit]: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

But all that changed at the beginning of the 20th century.

As our knowledge of architecture and construction grew, it became far too complex for any one person to handle. It was beyond human capacity for one person to be “master” of it all. Instead, a profusion of specialists took the place of the master builder: architects, engineers, brick and stonemasons, glass technicians, electricians, and the list goes on—all experts of their own domains. And it’s not just construction. As human knowledge grows ever deeper and more complex, similar transformations have occurred across nearly every field, from medicine to business. In order to succeed in today’s knowledge economy, we don’t need master builders—we need specialists who can work together, joining their expertise to solve complex problems collaboratively. We need strong, collaborative teams.

The state of team collaboration

While there’s a growing recognition of the importance of teamwork in completing ambitious projects, we have a very human tendency to celebrate remarkable individuals over group achievement. Nowhere is this more evident than in Silicon Valley. There, the narrative of the lone genius proliferates. Companies seek to hire “10x-ers” and brilliant engineers aspire to become household names like Elon Musk (despite his sometimes questionable tweets).

Yet research suggests the lone genius is a mythical figure—or at least, an exaggerated one. As a Harvard Business Review (HBR) article reports, a brilliant new idea or discovery is only the first step of many: “For any innovation to have an impact, there needs to be a discovery on an important insight; a viable, scalable solution; and, finally, a business model that allows the new idea to be adopted.” And crucially, innovators rarely act alone: In order to succeed, they need teams to support them.

It’s a misconception that comes from how we’ve historically treated work. While team collaboration is as old as humanity itself—humans have been working together in groups since our hunter-gatherer days—teamwork in the workplace is new. When the modern concept of work emerged around the time of the industrial revolution, companies organized around individuals, not teams. It’s only as our world has grown more complex that organizations have restructured once more around groups.

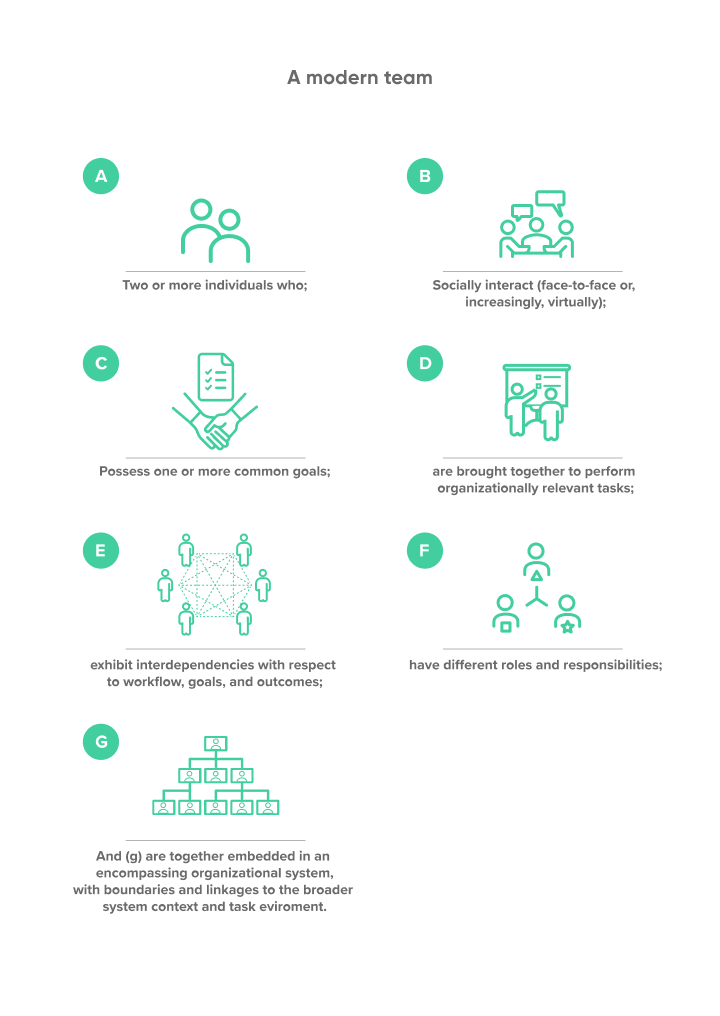

This return to a team-based structure is strategically significant. It “enable[s] more rapid, flexible, and adaptive responses to the unexpected,” according to organizational psychologists Steve W.J. Kozlowski and Daniel R. Ilgen. They define a modern team as:

(a) Two or more individuals who; (b) socially interact (face-to-face or, increasingly, virtually); (c) possess one or more common goals; (d) are brought together to perform organizationally relevant tasks; (e) exhibit interdependencies with respect to workflow, goals, and outcomes; (f) have different roles and responsibilities; and (g) are together embedded in an encompassing organizational system, with boundaries and linkages to the broader system context and task environment.

Why is team collaboration important?

Probably the most important thing I’ve learned up here is the importance of teamwork.

—NASA Astronaut Douglas Wheelock

Team collaboration is at the heart of everything we do as a species, both in terms of work and family life. Strong teamwork has enabled us to accomplish incredible things, like the Apollo 13 mission, the greatest space rescue in history. But poor teamwork has also caused enormous tragedy and suffering, like the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) slow and disorganized response to Hurricane Katrina. And the stakes are high: “Failures of team leadership, coordination, and communication are well-documented causes of the majority of air crashes, medical errors, and industrial disasters,” note psychologists Kozlowski and Ilgen in their research.

Failures of team leadership, coordination, and communication are well-documented causes of the majority of air crashes, medical errors, and industrial disasters.

—Psychologists Steve W.J. Kozlowski and Daniel R. Ilgen.

The modern business landscape also faces unique pressures that make teamwork more important than ever for economic success. Competition and consolidation are on the rise, forcing companies to become more innovative, agile, and adaptive. In order to meet these challenges, organizations need to bring together groups of highly skilled individuals to solve problems and invent new solutions. Team collaboration is essential for success in today’s economy.

Benefits of team collaboration

In addition to increased agility and competitive success, team collaboration provides numerous other benefits for businesses and employees. These include:

Employee happiness

Humans are social animals—so it’s not surprising that positive, collaborative relationships are an important component of workplace satisfaction. A Taipei Medical University study found that collaborative relationships are among the top two most important predictors of job satisfaction among healthcare providers. The other is high-quality patient care. Employees are happiest when they feel like they’re part of a high-functioning team doing good work.

Innovation

While the myth of the “lone genius” proliferates in our society, emerging research suggests that it’s diverse teams, not solo innovators, who actually make progress and disrupt the status quo. According to research by social scientist Scott E. Page, teams with a range of different perspectives—including professional backgrounds as well as demographics—outperform groups of like-minded thinkers. When all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, but a diverse team has a whole toolbox.

Teams with a range of different perspectives—professional backgrounds as well as demographics—outperform groups of like-minded thinkers.

Greater productivity

Two heads really are better than one. An American Psychological Association (APA) study of teamwork in the military found that a cohesive team (i.e., one in which there are strong bonds among team members) is more effective than the sum of its individual members. “Teams can absorb more task demands, perform with fewer errors, and exceed performance based on linear composites of individual performance,” study authors Gerald F. Goodwin, Nikki Blacksmith, and Meredith R. Coats write. In short, a strong team consistently outperforms the sum total of the same individuals working alone. Want a more productive team? Work on their collaboration skills.

Customer orientation

According to a McKinsey study, diverse teams that represent their customer base in terms of demographic distribution are better able to reach their audiences and empathize with customers. This is of key strategic importance, as the business landscape is increasingly heterogeneous: Women make 70-80 percent of purchasing decisions, and the purchasing power of minority ethnic groups as well as LGBTQ+ folks is on the rise. “A top team that reflects these powerful demographic groups will have a better understanding of their market decision behavior and how to impact,” concludes McKinsey.

Understanding team effectiveness

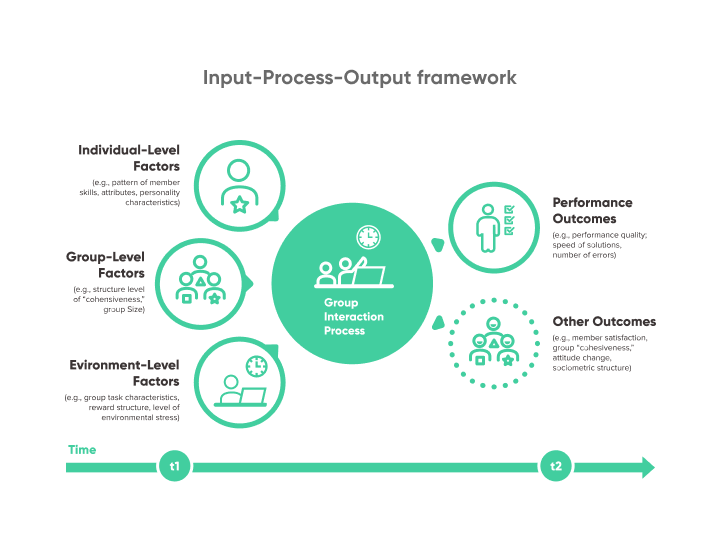

Psychologists J. Richard Hackman and Charles G. Morris devised one of the most common models for understanding how teams function in the 1970s, the Input-Process-Output (IPO) model. The model demonstrates that many individual, environmental, and group factors can influence a team’s productivity and cohesiveness.

By measuring productivity using this model, organizations can understand what factors influence team performance and how to help teams to perform better. Broadly speaking, organizations can optimize team performance by tweaking a team’s inputs or changing their group interaction processes.

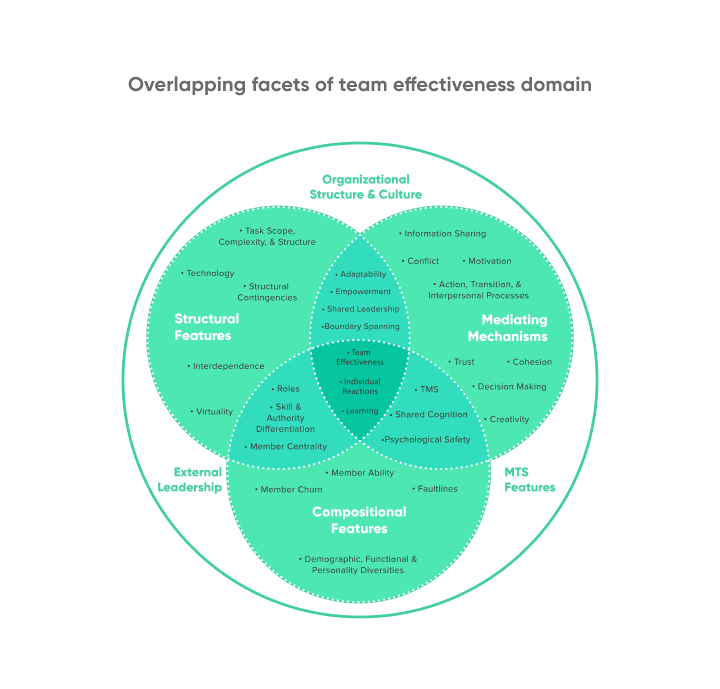

While the IPO model is still useful for understanding team interactions, there has been growing recognition that reality is often more complex than the model. In 2017, a group of psychologists updated and expanded Hackman and Morris’ model. Rather than thinking of team effectiveness as a series of inputs and processes, they encapsulated it as groupings of facets that overlap and inform one another.

While less straightforward, this model better summarizes the complex network of factors that goes into team effectiveness. In the next section, we’ll highlight some key features and their role in creating effective teams.

The term teamwork has graced countless motivational posters and office walls. However, although teamwork is often easy to observe, it is somewhat more difficult to describe and yet more difficult to produce.

—James E. Driskell, Eduardo Salas, and Tripp Driskell, Foundations of Teamwork and Collaboration, APA 2018

While everyone agrees that teamwork is desirable, management gurus and thought leaders differ on what successful team collaboration looks like and how to get there. It’s a challenging topic since individual teams can vary widely. However, psychologists—like the researchers behind the “overlapping facets of team effectiveness domain”—have identified core qualities that all teams share which in turn feed into their outcomes. We’ll investigate some of the most important elements below.

The basics of successful team collaboration

Shared mission

At its most basic, every team must have an objective—a product they’re building, a strategy they’re developing, or a problem they’re trying to solve.

Criteria for success: Set clear and specific goals

In order to succeed, this purpose must be clearly articulated. We know that goal-setting is linked to higher achievement in individuals, and the same is true in teams: Research shows that goal clarity positively affects team performance. Goal-setting may look different between organizations—some teams may use a Waterfall approach and outline all their goals at the outset of a project. Other teams may be more Agile and add or adjust goals on a rolling basis. Both approaches work as long as teams clearly articulate their goals and the criteria for their achievement.

Organizational culture

According to a Northwestern University study, culture is “a set of norms and values that are widely shared and strongly held throughout the organization.” All teams have a set of beliefs and norms, whether implicit or explicit, which form the social environment in which they operate.

Criteria for success: Foster an environment of psychological safety

Culture determines a team’s ability to be innovative, take calculated risks, and learn from their mistakes. Teams in which members feel free to express observations and voice their opinions are better poised to achieve their goals. Psychologists use the term “psychological safety” to describe this phenomenon. “Psychological safety describes people’s perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a particular context such as a workplace,” according to one Harvard Business School study. People who feel psychologically safe are more likely to share knowledge instead of hoarding it, voice suggestions, and spearhead new initiatives. In short, they’re more engaged team members.

Team size

Every team is composed of a certain number of members. Increasingly, research shows that team size determines the team’s outputs—whether they develop existing ideas or disrupt the status quo.

Criteria for success: Keep teams as small as possible

A recent Nature paper looked at 65 million team outputs—research papers, patents, and software products—in the fields of science and technology to discover how these outputs change between large and small teams (they define “small” as three people or less). Their findings: “Whereas large teams tended to develop and further existing ideas and designs, their smaller counterparts tended to disrupt current ways of thinking with new ideas, inventions, and opportunities,” noted the researchers. You’re more likely to take risks and be original when you’re in a small team. To maximize innovation, keep team size to a minimum.

You might protest that some projects are outside the scope of a small group of individuals. You need more than three people to build a rocket or develop a successful vaccine. “High-impact discoveries and inventions today rarely emerge from a solo scientist, but rather from complex networks of innovators working together in larger, more diverse, increasingly complex teams,” according to the researchers. In order to manage these kinds of projects, organizations should create “multi-team systems” (MTSs) in which small teams are embedded in a larger network of teams working together on different aspects of the same problem. Many scientific collaborations are organized this way, with small groups of researchers at different universities forming a larger team working towards a specific goal, like searching for dark matter.

Member ability

Every team is a collection of individual members with their own unique skills, abilities, strengths, and weaknesses.

Criteria for success: Form teams around complimentary KSAOs

KSAOs stands for knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics. Great teams are composed of members who complement each other’s strengths and balance their weaknesses. “In an ideal situation, organizations could recruit, select, and compose teams with an optimal mix of members’ KSAOs,” write researchers. However, reality is usually more complex. It’s not always possible to form teams based on member ability, and team members may come and go. However, there are ways in which organizations can foster these complimentary KSAOs, such as by augmenting members’ existing skills with training.

Teamwork tools and practices

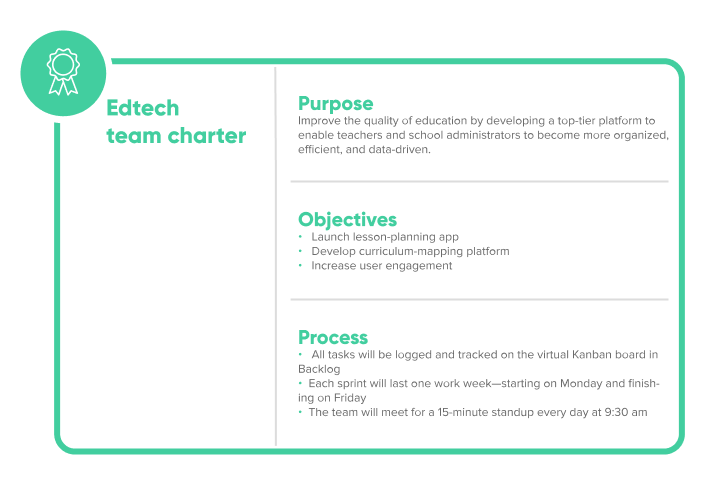

Team charters

Team charters are documents that teams create when the members initially form a team, outlining the purpose of the team (the “why”), how they plan to work together (the “how”), and their end goals (the “what”). Some team charters also include success metrics. Researchers have found that when teams make use of charters, they experience improved process outcomes, including better “communication, effort, mutual support, cohesion, and member satisfaction.” By putting your team mission in writing, you create a foundation for successful collaboration.

Example team charter for an Edtech product team:

Planning

Planning is essential to team success. Whether sweeping and strategic, like the company direction for the next five years, or limited and granular, like a new feature, it provides direction for the team and objectives to work toward. (And we’re already covered how essential goal-setting is for teams). Even agile teams, who might not follow a plan in the traditional sense, create task backlogs and set goals—they just tend to recalibrate their priorities more frequently to be flexible and responsive to change.

Team psychology researchers have identified some core elements of high-quality planning. These include:

- Effective communication among group members

- A future orientation—that is to say, the extent to which you can imagine the future, anticipate consequences, and plan ahead

- A systematic understanding of the team or organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (also known as SWOT analysis)

Regardless of the size or scope of your task, if you’re able to analyze your current position, think critically about the future, and communicate effectively with your team, you’ll be in the best position to make a high-quality plan.

Measurement

“What gets measured, gets managed”—the most famous thing management theorist Peter Drucker never said—is a favorite cliché of managers and consultants. And there’s some truth to it. While not everything that matters can be measured (and for that matter, not everything we can measure matters), it can nonetheless provide useful insights. The trick is identifying what to measure. For instance, a measurement might not adequately capture your team’s enthusiasm, but it can capture whether you’re on track to reach your goal of releasing five new features this month.

There are a variety of approaches teams can use to measure progress toward their goals. One such approach is using Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Teams set targets and then measure their progress based on leading KPIs, indicators that may indicate future success, and lagging KPIs, which show past success. For instance, if a content team’s goal is to publish fifty blog posts this quarter, their lagging indicator might be how many blog posts they published last month, and their leading indicator might be how many blog posts they have started working on this month. Good KPIs should measure what is intended, show evidence of advancement, and utilize a balance of both leading and lagging indicators to capture progress.

Other approaches are more visual. For instance, teams can use Gantt charts to lay out their tasks’ start and finish dates on a calendar, giving them a bird’s-eye view of their project progress. Or, they can use burndown charts to graph the amount of work they need to get done versus the amount of time they have to do it in. Any of these measurement systems can be effective—which one you choose depends on your team’s needs and preferences.

Reviews and debriefings

Originating in the military—where teams frequently need to evaluate past performance and make adjustments on the fly—debriefing is a reflective tool that allows teams to recalibrate their approach as they go. It’s “a structured learning process designed to continuously evolve plans while they’re being executed,” writes Doug Sundheim for the HBR. And it’s effective: Psychologists have found that organizations can improve team performance by 20-25 percent by conducting effective reviews and debriefs.

Depending on the team, these reviews may vary in length and frequency. For instance, many teams have daily standups, essentially mini-debriefings, reviewing yesterday’s achievements and today’s goals. Other teams host debriefings after completing major project milestones called post-mortem meetings. Either approach can work, but Sundheim recommends having at least one team debriefing at a set time each week to make it habitual.

To have an effective debriefing, team members must, to borrow a military idiom, ”leave their stripes at the door”—that is to say, abandon status and ego in favor of vulnerability and curiosity. While it may be more uncomfortable at first, having an open conversation about the root causes behind your team’s successes and failures will result in more learning in the long run.

Now that we’ve covered the theoretical, it’s time to get practical. In this section, we’ll delve into the practical strategies you can use to foster a culture of collaboration in your team.

Cultivate collaboration

Shift perspective by rallying around a shared mission

“Collaboration may be a practice—a way of working in harmony with others—but it begins with a point of view,” writes Tony Award-winning choreographer Twyla Tharp in The Collaborative Habit. Effective collaboration begins as an internal state: Thinking in terms of “we,” not “I.”

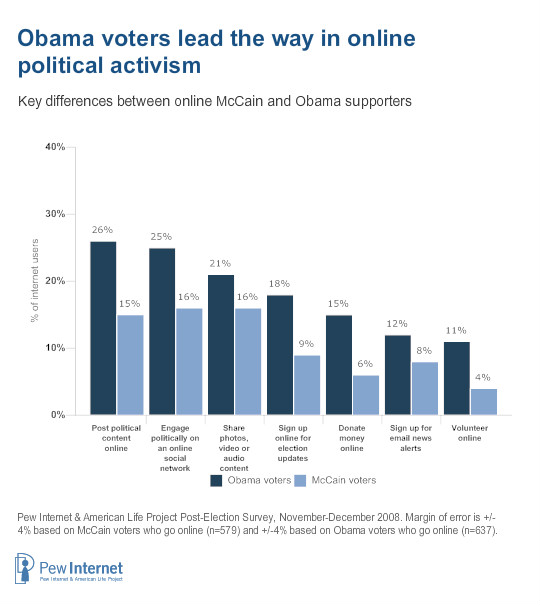

A prime example of the power of this kind of collaborative thinking is Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Though surveys from the time show that Republicans were more likely to be active internet users, Obama’s online campaign generated significantly more traffic than his opponent John McCain’s. The reason? Rallying around the campaign slogan “Yes, we can,” Obama’s supporters took matters into their own hands—sharing, promoting, and engaging with the campaign online.

Obama’s campaign shows the power of a perspective shift—yes, we can. But such collaborative thinking can only occur when team members have a shared purpose. This is where a shared mission comes in. A larger goal, outside of a team’s individual members, provides an external focus—something to orient their attention and unify their focus. If your team struggles to function collaboratively, think about your purpose. Do you have a shared mission that everyone understands and supports? If not, work to define it into something that everyone is enthusiastic about.

Give team members autonomy

Teams function best when their members can act as experts of their own domains rather than the recipients of orders. Take the example of Hurricane Katrina. FEMA’s response to the crisis has been widely studied and criticized by experts—tangled in a bureaucratic, command-and-control system, government officials were prevented from responding quickly and supplying resources effectively. This exacerbated the disaster and caused needless suffering.

But an unlikely hero emerged in the wake of the hurricane: Walmart. Instead of pushing decisions up the hierarchy, Walmart empowered its staff to act independently. “A lot of you are going to have to make decisions above your level,” CEO Lee Scott told his employees. “Make the best decision that you can with the information that’s available to you at the time, and, above all, do the right thing.” Walmart staff set up temporary distribution centers, supplying much-needed essentials to displaced residents. They raided their pharmacies to supply hospitals with necessary drugs. They gave hatchets, ropes, and boots to rescue workers. While the government was still fumbling its response, Walmart employees were taking action.

“The philosophy is that you push the power of decision-making out to the periphery and away from the center,” writes Atul Gawande, in The Checklist Manifesto. “You give people the room to adapt, based on their experience and expertise. All you ask is that they talk to one another and take responsibility.” When you push power away from the center, you empower team members to use their expertise most effectively—resulting in a high-functioning team.

Lead by example

By this point, “lead by example” is the stuff of managerial cliché—but it’s become cliché because it’s true. It’s not just anecdotally compelling, there’s science to back it up: “For a social norm to be enforced it must be shared by most people in a community. In particular, in a firm, it must be shared and followed by who is at the top,” write the authors of a Northwestern University study on corporate culture. If you want strong collaboration to become a core part of your organization, you have to model that behavior. As the research demonstrates, culture comes from the top.

Establish healthy boundaries

Boundaries create social norms: This is okay, this isn’t okay—here’s where we draw the line. In interpersonal relationships, they allow people to feel respected and safe. In the workplace, they also perform the important function of allowing team members to do their best work. Teams should especially consider implementing boundaries that protect employees’ time and space. For instance, maybe a team boundary is that no one interrupts their colleagues while working with headphones, allowing them to focus completely on the task at hand. Or to set up a meeting, you need to send a brief meeting agenda to all invitees to ensure the meeting is necessary.

If your team hasn’t clearly defined these boundaries, you can still carve them out gently for yourself. For instance, if someone books a meeting on your calendar without asking you first, follow up and ask what the goals for the meeting are. This ensures you’re spending your time effectively and sets a precedent that meetings with you should have a defined goal.

Encourage vulnerability

Teams learn from their failures, not their successes. Understanding what went badly—and how you can do better—is typically more illuminating than what went well. To encourage your team to be open and honest about their shortcomings, creating a culture that celebrates failure is key. Failure means you’re trying new things and learning—it’s the only pathway to growth. One way to do this is to create an “oops” wall (a chat channel will do as well). Whenever something doesn’t go according to plan, make it a practice to record it on your “oops” wall. This helps normalize vulnerability and encourages team members to grow from their mistakes—not hide them or cover them up.

Common teamwork challenges (and how to fix them)

The problem: Communication difficulties

The fix: Implement check-ins and check-outs

This is a strategy used by surgery teams in the operating room. Because the same teams don’t always work together, researchers found that the members of an operating team sometimes didn’t even know each other’s names. To rectify this, they implemented the check-in: Before an operating team begins a procedure, the team goes around in a circle, introducing themselves and their roles. In addition to ensuring that everyone feels comfortable communicating with one another, these check-ins also seemed to help engage members’ participation and encourage less senior members of the group to speak up when they had something important to say—for instance, a nurse contradicting or challenging a senior doctor when they noticed something wrong. Researchers call this the “activation phenomenon.” “Giving people a chance to say something at the start seemed to activate their sense of participation and willingness to speak up,” writes Dr. Atul Gawade, a surgeon, in The Checklist Manifesto.

Try it yourself: While you might not need to have your team members introduce themselves at every meeting—especially if they always work together, unlike frequently-changing operating room teams—it’s still useful to go around and give everyone the chance to give their input. Try starting every meeting by having everyone share a quick progress report or telling the team something that went well in the last week. Find the check-in questions that are right for your team and your situation.

The problem: Vague or unclear expectations

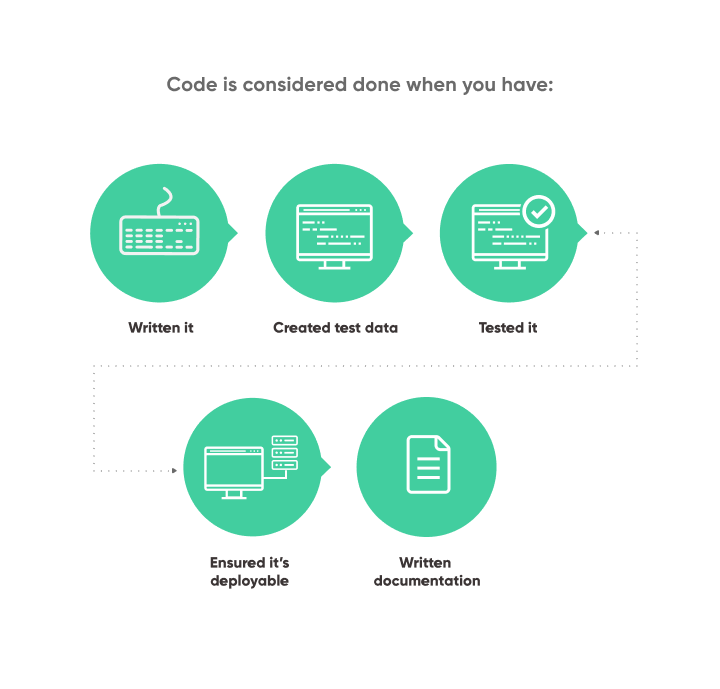

The fix: Create a shared definition of done

“Done” can mean many things to many people. For instance, to a developer, a piece of code might be ‘done’ when it’s written; to a QA person, when it’s tested; and to a DevOps person, when it’s shipped. Vagueness associated with a team’s responsibilities can result in competing interpretations. That’s why many teams create a “definition of done”—a technique borrowed from Agile methodology. Your definition should include all the steps a task needs to pass before it can be considered done. For instance, a development team might adopt the following definition.

Try it yourself: Create a “done” checklist that your team members can refer to. If your team is responsible for different kinds of tasks, you may need to create separate checklists for each. That way, when someone says, “I’m done,” you’ll know exactly what they mean.

The problem: Hierarchical structures

The solution: Empower your team

Big organizations typically have large and complex hierarchies. There can be a lot of bureaucracy beyond the team’s control—such as unnecessary meetings or excessive emails—that wastes time and prevents team members from doing their best work. Team members may struggle to voice these concerns as they don’t want to upset the hierarchy. Therefore, it’s up to managers to empower employees to carve out the time and space they need to thrive in their positions.

Try it yourself: Implement the “law of two feet”—if you aren’t contributing or learning something of value to you in a meeting, you are free to go. This allows team members to absorb value where they need it and prioritize other tasks if they are more important.

Advice for remote teams

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, remote working was on the rise—and research suggests the trend will continue after we find ways of managing the virus. But dispersed teams, whether working partially or entirely remotely, face unique challenges when collaborating remotely, leading remotely, managing remotely, brainstorming remotely, and hosting meetings remotely. Here’s our advice for instilling a sense of team cohesion and maximizing productivity, even when you’re apart.

Create a sense of belonging

As noted in the first section of this guide, research has found that professionals find their relationships with colleagues to be some of the most rewarding aspects of their work. Bringing together diverse team members to work with and learn from each other also frequently plays a role in innovation.

In order for remote team members to share these benefits, it’s important to create a sense of community and facilitate spontaneous connections. Remote teams need to be more intentional than in-person teams about facilitating social and team-building activities, but these don’t have to require a ton of effort or planning. Casual, daily opt-in activities over video chat, such as a team stretch or afternoon coffee break, gives team members the chance to take a well-deserved pause, get to know their colleagues in a casual setting, and maybe even make a new friend. Adjusting to the drastic work changes we’re all experiencing with positive, new habits can help teams establish their own satisfying remote work culture.

Choose the right tools—and ensure team members use them correctly

Every team needs a project management framework to understand their tasks and keep them on track—and for remote teams, this is even more essential. Digital project management tools like Backlog provide remote teams with a single source of truth for their work, allowing them to view their progress, collaborate with coworkers, and stay on track. Project managers have the benefit of being able to see everyone’s progress on one dashboard, giving them a high-level overview of project status.

But in order to be effective, it’s crucial team members are on the same page with how they use these tools. For instance, you can use your shared “definition of done” to ensure team members only check off tasks once they are well and truly complete. You may also need to set expectations for how tasks are added to your backlog. As a team, set some ground rules about how you will use the tool to be most effective.

Make use of both synchronous and asynchronous communication

Video calls are great for important discussions, decision-making, and brainstorming sessions. Especially when those video call features are built right in to a collaborative online whiteboard like Cacoo. But they can also be troublesome to coordinate if your team is spread across multiple time zones, and we all have to be more cognizant of one another’s risk for video call fatigue. If you simply need to communicate information, using a team chat app can be a welcome alternative.

Be human

It can be a challenge to create a remote work routine for the first time—especially if you’re doing so with the added stressors of a global pandemic. Have patience with yourself and with your colleagues. Normalizing failure and encouraging vulnerability are even more essential as we all grapple with these changes.

Conclusion

As our work grows increasingly complicated and specialized, teamwork and collaboration emerge as critical skills. In today’s workplace, we don’t need master builders—we need teams of experts who can join forces to reach audacious goals. By learning to implement the teamwork tools, practices, and strategies discussed above, you’ll be well on your way to fostering high-functioning, collaborative teams—whether in-person or remote.

Looking for a tool to help support your team collaboration? At Nulab. we create collaboration tools for teams to help them manage projects, communicate easily, and collaborate in real-time. You can check out our collaboration tools here.

Further Reading & Recommended Resources

Books

- The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies by Scott E. Page

- The Collaborative Habit by Twyla Tharp

- The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande